Every game designer has their own list of essential games that, in their opinion, everyone who wants to understand the profession should play. Some have Super Mario Bros., others Dark Souls, some even remember Candy Crush Saga.

My list is subjective, like any other. But each game in it is a lesson in game design, written in sweat, blood, and pixels.

1. Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain — A Masterclass in Systems Design

Lesson: How to create a game where every mechanic works in conjunction with the others, and the player chooses how to play.

In fact, MGS V is two games in one. Ground Zeroes is a demo, prologue, and important narrative link to Peace Walker. An excellent way to spend 10 hours on a 2-hour game if you try all the variations of completion. And The Phantom Pain is the main game that could have been perfect if Kojima hadn’t been fired from Konami before its completion.

Thoughtful Progression System

The first thing that strikes you is the feeling of complete immersion. You don’t notice where the cutscene ends and gameplay begins. Everything looks so natural that in 2014, for the first time, the thought creeps in: “Why do we even need to develop graphics further?”

You start the game as a pathetic failure. Literally — your character can’t even walk properly, crawling through hospital corridors while everything around burns. But gradually, mission by mission, you level up to a super soldier who can:

- Become invisible

- Call in airstrikes and artillery support

- Use futuristic gadgets

- Control mechs (yes, there are mechs in a stealth game!)

The entire journey from worthlessness to god of war is implemented so smoothly that you don’t even notice. As soon as you think: “I could really use the ability to mark enemies now,” — the game immediately gives you access to this mechanic through base development or new equipment, or simply story progress.

Hundreds of Mechanics Without a Single Tutorial

MGS V has an insane number of ways to complete any task:

- You can complete missions absolutely stealthily without killing a single enemy

- You can arrange a total cleanup with a grenade launcher

- You can play Pokemon — knock out enemies and send them to your base with balloons (Fulton system)

- You can lure enemies with inflatable decoys or sound distractions

- Or you can just call in a helicopter with loudspeakers, turn on Ride of the Valkyries and shoot everyone from the air

And I haven’t even mentioned the ability to:

- Use cardboard boxes for camouflage (with different pictures!)

- Call in sandstorms for stealth

- Use your horse as mobile cover

- Make enemies fight each other

Kojima gives the player maximum freedom of action, while somehow miraculously preventing them from breaking the game. This is the highest level of balance — when the player feels omnipotent, but the game still challenges them.

Meta-game as Part of Core Gameplay

Mother Base development isn’t just an additional activity. Everything you find in the open world, all the resources you steal from enemies, every kidnapped specialist — all of this directly affects your capabilities in the field.

Found blueprints for new weapons? You need R&D specialists of a certain level. Want to unlock invisibility? Level up the medical unit. Need air support? Develop the combat unit.

And the most ingenious part — this system works both ways. Enemies adapt to your playstyle. Often landing headshots? They’ll start wearing helmets. Prefer night raids? Expect searchlights and night vision devices. The game constantly forces you to change tactics.

A Serious Story That Remembers It’s a Game

MGS V manages to tell a story about war, betrayal, nuclear deterrence, and phantom pain (both physical and metaphorical), while not forgetting that games should entertain.

You can deeply experience moral dilemmas… and then put on a chicken helmet that makes enemies less vigilant. Or use a rocket arm for quick prisoner capture. Or make your horse defecate on the road to make enemy vehicles skid.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Systems are more important than individual mechanics. Every element of the game is connected to the others. No isolated features.

- Player freedom doesn’t mean absence of rules. On the contrary, the more freedom, the more thoughtful the limitations must be.

- Progression should be felt, not imposed. The player chooses their own development direction.

- Adaptability creates replayability. A game that changes in response to player actions stays interesting longer.

- Seriousness and absurdity can coexist. The main thing is the internal logic of the world.

2. XCOM 2: War of the Chosen — The Gold Standard of Tactical Strategy

Lesson: How to create a game where every decision has weight, and defeat makes victory sweeter.

XCOM 2: War of the Chosen is not just a tactics game about aliens. It’s a simulator of strategic despair, a generator of personal dramas, and a guide to creating systemic games that bend the player over backwards, but do it so elegantly that you want to thank them.

Genius Progression System

At the beginning of the game, you have a squad of crooked rookies who can miss an enemy with a 95% chance while standing two tiles away from them. This isn’t a bug — it’s a feature. The game deliberately makes the beginning humiliating so that progress feels more acute.

Gradually, these incompetents turn into legends:

- Sniper Volkova, who saved the entire team with an impossible shot across the entire map

- Ranger “Ghost” Thompson, master of the blade, who personally cut down three Chosen

- Psionic Zhang, whose mind control turned the tide of the final battle

Each soldier is not just a set of characteristics. It’s a small story with scars (literally — the game remembers injuries), psychological trauma, and personal achievements. When such a soldier dies, it’s not a unit loss — it’s a tragedy.

And most importantly: the stronger your squad becomes, the smarter and more dangerous the enemies become. The game uses a dynamic difficulty system that analyzes your progress and throws new challenges exactly when you start feeling confident.

Procedural Generation as Art

Most missions in XCOM 2 are procedurally generated, but you’ll never feel like you’re playing “random”. The secret is in the thoughtful system.

Block-based level generation. Maps are assembled from pre-made “plots” about 10×10 tiles in size. These plots can rotate, mirror, and combine in many ways. A two-story building can stand next to a park, which borders a gas station.

Multi-layered randomization:

- Mission type: VIP rescue, data hack, object destruction, etc.

- Biome: city, suburbs, wasteland, sewers

- Time of day and weather (affect visibility)

- Season — allows visual variety without creating additional assets

- Types and number of enemies

- Patrol placement

- Reinforcement spawn points

- Additional objectives and rewards

- Probability of Chosen and Alien Rulers appearing

- Chosen modifiers

As Jake Solomon, the game’s creative director, said in one interview: “It’s a sort of tug of war: You want the players to feel like they have enough agency not to get screwed by the game. But you still have to make it an organic experience where the player is facing new challenges, so he has to respond with new answers. That’s really what procedural generation gets you: An unending experience.”

Balance That Withstands Madness

The internet is full of videos where people complete campaigns:

- With only snipers (imagine 6 people with rifles in close combat)

- With only basic recruits without class promotion

- Without any losses on maximum difficulty

- With one immortal soldier

And this isn’t cheating or exploits. The game really allows such experiments because the balance is built on several levels:

- Classes complement but don’t replace each other. Yes, a squad of only snipers is possible, but it will require a complete tactical rebuild.

- Equipment can compensate for weaknesses. No medic? Take medkits. Low damage? Grenades solve problems.

- Environment is your ally. Blow up walls, create cover, use height.

Emotional Involvement Through Mechanics

XCOM 2 masterfully creates attachment to characters without a single line of written dialogue. How?

Customization. You can customize the appearance, biography, even the voice of each soldier. My sniper Volkova? She looks like my friend and speaks with a Russian accent.

Relationship system. Soldiers who often go on missions together become “bonded”. They get bonuses fighting side by side, but go into a rage if their partner is wounded.

Memorial to the fallen. Every fallen soldier is entered into a memorial with the date, place of death, and the enemy that killed them. At the end of the game, you’ll be shown everyone who didn’t live to see victory. And suddenly that same Johnson who missed a sectoid from two tiles becomes part of your personal war story.

The Chosen as a Narrative Pacing Tool

The War of the Chosen expansion introduces three unique enemies — the Chosen. These aren’t just bosses, they’re characters with their own personalities, strengths and weaknesses:

- Assassin — master of stealth and melee combat

- Warlock — psionic capable of raising the dead

- Hunter — sniper with invisibility and traps

But the main thing — they appear at random moments during regular missions, completely changing the situation. You’ve almost completed the objective? The Hunter appears and starts picking off soldiers. Retreating under fire? The Assassin jumps out of nowhere and stuns your best fighter.

And they learn. After each encounter, the Chosen gain information about your tactics and will be ready next time. Used a lot of explosives? Get explosion immunity. Relied on psionics? Meet the mental shield.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Loss is part of the experience. Don’t be afraid to kill player characters if it makes victory more meaningful.

- Procedural generation requires manual work. The more quality blocks, the better the final result.

- Emotions can be created through mechanics. No need for expensive cutscenes if the player will create their own story.

- Difficulty should grow with the player. A static difficulty curve leads to boredom.

- Give players tools for self-expression. Customization is not just cosmetics.

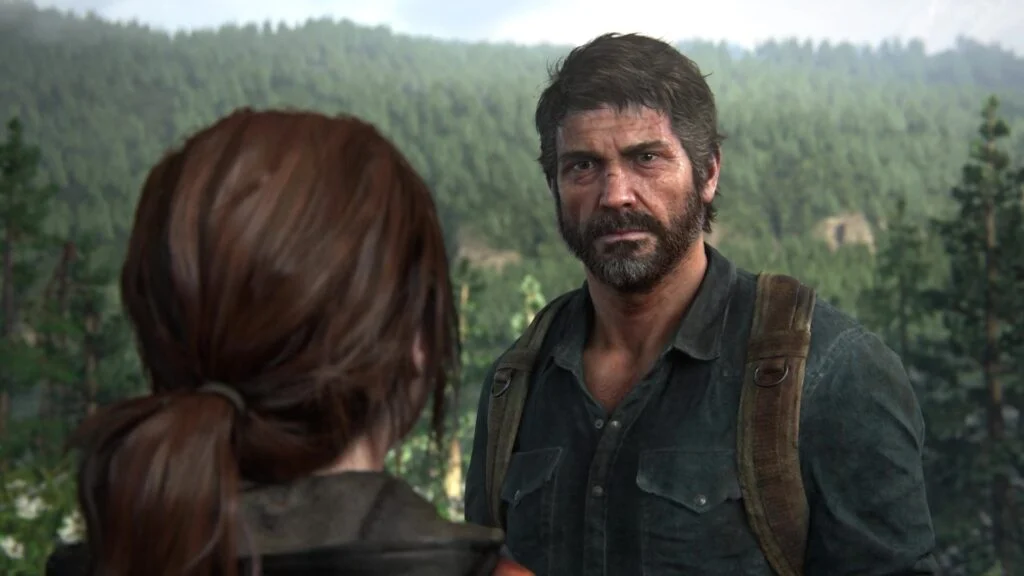

3. The Last of Us Series — Obsession with Details

Lesson: How to bring every aspect of a game to perfection and why it matters.

Everyone knows The Last of Us for its story. The prologue of the first part won more awards than most films. Naughty Dog plays on the heartstrings so masterfully that even the most hardened gamers shed tears. But today let’s talk not about the narrative, but about the technical side — that obsession with details that makes Naughty Dog a legendary studio.

Weapon and Crafting System in Part One

At release in 2013, the first The Last of Us did several things better than anyone in the industry.

Each weapon had character. It’s not just damage numbers. The shotgun kicks with such recoil that Joel barely holds it. The revolver is heavy and unwieldy, but hits for sure. The bow requires time to draw but works silently. But most importantly, each is maximally realistically animated, even for modifications.

Real-time crafting. The game didn’t pause when you created a medkit or Molotov cocktail. Enemies continued searching for you while you frantically wrapped bandages. This created tension.

Upgrades as part of survival. Found parts could be spent on weapon improvements, but choices were limited. Increase magazine capacity or reduce recoil? Add a silencer or increase damage? Each decision changed the playstyle.

Adaptive Resource Balance

The Last of Us uses an invisible “dynamic director” system (similar to Left 4 Dead, but more subtle):

- Playing aggressively and spending lots of ammo? You’ll find slightly more ammunition in the next locations

- Prefer stealth and conserve resources? The game will provide fewer items, maintaining tension

- Dying often in one place? An extra medkit or couple of bullets will appear

The system works so delicately that the player doesn’t notice it. There’s no feeling that the game is “giving in” — you just luckily found ammo at the right moment.

Revolution in Part Two

The Last of Us Part II raised the bar even higher.

Verticality and arena size. Locations became huge. Some areas are practically mini-sandboxes where you can:

- Go around enemies on rooftops

- Crawl through grass

- Use buildings for ambushes

- Set different factions against each other

Downtown Seattle is a prime example. It’s practically an open world in miniature, with optional locations, secrets, and multiple paths to the goal.

Dogs as a game mechanic. Enemies use dogs that track by scent. This completely changes familiar stealth:

- Can’t just hide in grass — the dog will smell you

- Have to think about wind direction

- Can distract dogs with bottles or throw them off the scent by running through water

Next-level animations. Part II has about 300 unique death animations. Three hundred! And that’s just deaths. There’s also:

- Contextual item pickup animations (Ellie picks things up differently from shelves, tables, ground)

- Unique animations for each weapon type in different situations

- Procedural hit animations (bullet to shoulder makes enemy grab it)

- Environmental reactions (Ellie automatically ducks under low obstacles)

Ropes. Those damn ropes. Anyone who’s tried to implement realistic rope physics in games knows it’s hell. Naughty Dog did them perfectly:

- Ropes wrap around objects

- React to wind

- Have proper tension

- Can be used for puzzles and movement

Accessibility as a New Standard

Part II has over 60 accessibility options:

- Full interface narration for visually impaired

- Visual cues for hearing impaired

- Simplified controls for people with disabilities

- High contrast mode

- Auto-aim of varying degrees

- Skip difficult sections

These aren’t just checkboxes in a menu. Each option is thought out and tested with real people. This is now the standard all projects should strive for.

Details That Create Immersion

Guitar. Yes, that guitar mini-game. A full instrument simulation with real chords. You can play real songs!

Safes can be cracked by sound. No need to find the code — just listen carefully to the lock clicks. A small detail that few will notice, but it’s there.

Dynamic contamination. Ellie gets dirty realistically:

- Blood stays where it hit due to player actions

- Dirt accumulates gradually

- Water washes away contamination

- Snow sticks to clothes

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Details create immersion. Players may not notice 90% of your work, but they’ll feel the difference.

- Technical limitations are a challenge, not an excuse. Ropes are difficult? Do them right.

- Accessibility is not optional. It’s an obligation to players.

- Animations are gameplay. Proper animation conveys weight, inertia, danger.

- Polish distinguishes good games from great ones. Can crack safes by sound? No one will notice. But it’s right.

4. Heroes of Might and Magic III — An Imperfect Masterpiece

Lesson: Why games become cult classics despite their flaws.

“Heroes” is more than a game for the post-Soviet space. It’s a cultural phenomenon, part of the collective memory of an entire generation. My first PC game disc was “The Restoration of Erathia”, and I still remember the feeling when I first saw the intro.

Everyone and their dog has praised the game. Written dissertations about it, analyzed game loops, examined reasons for popularity. So today let’s take an unexpected turn — let’s criticize “Heroes” for their obvious and not-so-obvious flaws.

Balance? Never Heard of It

Unlike its contemporary StarCraft, where balance is calibrated to the last health point, HoMM3 is chaos:

Necropolis — walking imbalance. Necromancy allows raising skeletons after every battle. With the right artifacts and hero, you can raise more skeletons than enemies killed. Exponential army growth that doesn’t require gold. GG WP.

Magic solves everything. At high difficulty levels, there are exactly two tactics:

- Cast “Slow” on enemy units first turn

- Cast “Haste” on your units first turn

- Everything else is pointless

Except for a few specific builds. For example, “Death Ripple” and “Armageddon” spells with proper leveling and build kill the entire enemy army while preserving yours.

Useless units. Some creatures are so bad their only purpose is to be recycled into something useful:

- Peasants — future skeletons

- Imps — cannon fodder

- Troglodytes — just because

Hero imbalances. While some argue who’s stronger — Crag Hack or Tazar, others choose Orrin and suffer. The difference in hero strength is so great that some are simply banned in tournament play.

Cheating AI

Computer opponents in “Heroes” are dumb as bricks. They:

- Can’t properly develop towns

- Don’t understand artifact value

- Run back and forth aimlessly

To compensate, developers gave AI cheats:

- Sees entire map (knows where resources and artifacts are)

- Gets bonuses to gold and resources on high difficulty

- Can pass through guards impassable for players

This creates artificial difficulty that irritates rather than challenges.

Late Game Problems

The beginning of a HoMM3 game is a celebration:

- Explore the map

- Find treasures

- Fight neutrals

- Build towns

But the further you go, the more the game turns into logistical hell:

- 8 heroes to move every turn

- Chains for transferring armies between towns

- Endless artifact reshuffling

- Resource collection from across the map

By the end of a large map, one turn can take 15-20 minutes of pure logistics. With minimal interesting decisions — just mechanical work.

Map Generator — Separate Pain

The built-in RMG (Random Map Generator) creates maps that are:

- Unbalanced: one player gets all mines, another gets swamp

- Ugly: objects placed randomly

- Illogical: snow next to desert

- Monotonous: always the same structure

The community created their own generators that work much better. But the fact that such an important part had to be rewritten…

Why Do We Love It?

Despite all these problems, HoMM3 remains one of the most beloved games. Why?

Atmosphere. Paul Romero’s music, visual style, overall fairy tale feeling — all create a unique atmosphere that sequels couldn’t replicate.

Easy entry. Rules can be explained in five minutes. Interface is intuitive. Even a child can figure it out.

Depth. Despite simplicity, the game has enormous depth. Synergies of heroes, skills, artifacts, and armies create thousands of combinations.

Social aspect. Hot-seat mode made the game a social phenomenon. Entire families spent weekends passing the mouse to each other.

Modding. Horn of the Abyss and Wake of Gods gave the game a second life. The community is still active and creating new content.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Perfect balance isn’t always necessary. Sometimes imbalanced elements create interesting situations.

- Atmosphere is more important than mechanics. Players will forgive much if the world enchants them.

- Easy entry + depth = success. Easy to start, hard to master.

- Social mechanics extend game life. Hot-seat did more for popularity than any feature.

- Give tools to the community. Map editor and modding are why people still play 25 years later.

5. Gothic Series — European School of RPG

Lesson: How to create a living world in limited space.

In 2001, small German studio Piranha Bytes released Gothic — a game that laid the foundation for an entire school of European RPGs. Gothic, Gothic II, and the “Night of the Raven” expansion aren’t just games, they’re a manifesto about what RPGs should be.

World Without a Map

Gothic has no map. Rather, it exists, but you need to find and buy it. Until then, orient yourself however you can:

- By the sun (yes, it moves correctly)

- By landmarks like “go south from the old mine to the big tree”

- By memory

- Following NPCs: they actually walk, not teleport

And you know what? It works. Gothic’s world is remembered better than in games where you look at the minimap instead of the environment. After 20 hours of play, you know every path, every turn. Returning to the Valley of Mines from the first game in the second, you navigate intuitively — because it’s your home.

Respect for Player and World

Gothic doesn’t hold your hand, but doesn’t mock you either. The game respects your intelligence.

Learning through world, not tutorials. The first NPC you meet, Diego, will show you the way to camp. Along the way, he’ll explain the basics, but unobtrusively — just as a fellow traveler. Don’t want to listen? Go yourself.

World consistency. If an NPC says he lives in a house by the river — he really lives there. If he promises to meet you at the gates in the morning — he’ll be waiting exactly at the gates in the morning.

Daily routine for everyone. All NPCs live their lives:

- Get up in the morning and go to work

- Work during the day: smiths forge, guards patrol, hunters hunt

- Relax in the tavern in the evening

- Sleep at night

Want to trade at night? You’ll have to wake the trader. And he’ll be unhappy. Even if you’re a hero and recently helped him.

Combat System — Simple but Deep

Many criticized the controls in the first Gothic. Not without reason — they really are unusual. But they have internal logic:

- W — forward movement

- S — backward movement

- A/D — turns

- LMB or Ctrl + direction — attacks

Sounds wild? In practice, this creates a unique combat feeling. You’re not just pressing buttons — you’re choosing the direction of each strike.

The second part abandoned this in favor of more traditional controls. And it was the right decision — accessibility is important. But something magical was lost.

Leveling with Respect

In Gothic, you can’t just invest skill points in a menu. Want to learn to forge swords? Find a blacksmith, pay him, and he’ll show you. Want to fight better? Find a sword master. Want to skin animals? A hunter will teach you… for a price.

Each new weapon proficiency level isn’t just +5 damage. It’s new animations, new combo attacks, new possibilities. At level one, you hold a sword like a log. At level two — already looks like a warrior. At level three — you’re a blade master with unique techniques.

Verticality and Scale

Gothic’s world is small by modern standards. You can walk around the entire Valley of Mines in 20 minutes. But it feels huge.

Verticality. Locations are placed at different levels. Old Camp on a hill, mine below, secret places on cliffs. The path from point A to point B is rarely straight.

Content density. No empty places. Every cave hides something. Something interesting around every corner. No copy-paste dungeons — each location is unique.

Danger. At the beginning, most of the world is deadly dangerous. See a path into the forest? Wolves will eat you there. A cave? Orcs there will kill you in one hit. This creates natural barriers and makes exploration a reward for character development.

Solutions and Consequences

Almost every task in Gothic has multiple solutions. Example — quest for castle pass:

- Can complete Thorus’s task and get it honestly

- Can steal from Thorus’s chest

- Can bribe guard Skip

- Can find secret passage

- Can wait for gates to open and slip through

And this isn’t “choose option A, B, or C” from dialogue. These are real actions in the world. The game doesn’t suggest options — think and find them yourself.

Gothic’s Legacy

Gothic created a design school that can be seen in later European RPGs.

The Witcher (entire series) — Polish developers were clearly inspired by Gothic. A world where every NPC matters, where quests are solved differently, where player intelligence is respected.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance — Historical realism meets Gothic philosophy. Dense world, realistic NPCs, need to learn everything.

Divinity: Original Sin — Despite turn-based combat, same philosophy. Systems, variability, respect for player.

Baldur’s Gate 3 — Modern pinnacle of this philosophy. Every problem has a dozen solutions.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Small living world is better than large dead one. Size doesn’t matter if every meter is filled with meaning.

- Players are smarter than you think. No need to explain every mechanic. Give tools and let them experiment.

- Consistency creates immersion. If a guard says he stands post from morning to evening — that’s how it should be.

- Progression should be felt. New level isn’t +5 damage, it’s new possibilities.

- Limitations create interest. Dangerous world makes each new place a reward.

6. Warcraft III — Strategy That Spawned Genres

Lesson: How one right decision can change an entire industry.

In 2002, I got my first computer at home. And one of the first games was Warcraft III. I was amazed — for the first time, a strategy game evoked emotions similar to reading a good fantasy novel. For the first time in an RTS, I wasn’t just completing missions, but caring about characters, asking “what’s next?”

From Warhammer to Own Universe

The story is well-known: Blizzard wanted to make a game in the Warhammer Fantasy universe, but couldn’t agree with Games Workshop. As a result, two universes were born — Warcraft and StarCraft. And it benefited the world.

Chris Metzen, having honed his skills on Diablo and StarCraft, approached Warcraft III as an experienced writer. The result — one of the best stories in the RTS genre:

- Arthas’s fall from paladin to Lich King

- Illidan’s tragedy

- Orc redemption

- Night Elf awakening

Each campaign is a complete story with character development, twists, and emotional moments. Stratholme is still discussed — was Arthas right to destroy the infected city?

Heroes Change Everything

Warcraft III’s main innovation — full-fledged heroes in RTS. There were attempts before (like StarCraft), but here the concept flourished.

Hero isn’t a super unit. It’s a character with their own progression:

- Levels and skill points

- Inventory with artifacts

- Unique abilities and role in army

Hero is army center. All strategy revolves around heroes:

- Killing enemy hero often decides battle

- Hero abilities determine tactics

- Items can radically change balance of power

Hero is a character. In campaign, you go through Arthas’s entire journey with him. You’re not just controlling a unit — you’re seeing the story through his eyes.

Four Races — Four Philosophies

Unlike StarCraft with its three radically different races, Warcraft III took a different path.

Alliance — classic faction. Sturdy units, defensive play, powerful magic. If you’ve played any RTS, you know how to play Alliance.

Horde — brute force. Powerful melee units, shamanism instead of magic, aggressive style. Counter to Alliance in everything.

Undead — blight mechanics. Base builds on corrupted ground, units regenerate on it, corpses become resources. Unique expansion concept… of zerg.

Night Elves — harmony with nature. Mobile buildings, invisibility at night, powerful but expensive units. Most unusual race.

Balance between races isn’t perfect, but each plays uniquely. This is more important than mathematical equality.

Campaign as Tutorial

Warcraft III’s single-player campaign is a masterclass in teaching through gameplay.

Gradual mechanic introduction. Each mission adds something new:

- First — basic control

- Second — building

- Third — heroes

- And so on

Task variety. Not 30 missions of “build base and destroy enemy”:

- Position defense

- Stealth missions

- Time races

- RPG segments

- Large-scale battles

Story motivation. You’re not just completing tasks — you’re living a story. Defending Lordaeron not because you have to, but because it’s your home.

Map Editor — Separate Universe

World Editor from Warcraft III isn’t just a map editor. It’s a full game creation engine.

Power. Can change almost everything:

- Create new units

- Write complex scripts

- Change game rules

- Create cutscenes

Accessibility. Despite all the power, editor is intuitive. Simple map can be made in an hour. Masterpiece — in years.

Results. Editor spawned:

- Defense of the Ancients genre aka DotA/MOBA

- Tower Defense genre

- Hundreds of RPG maps

- Thousands of unique game modes

DotA became so popular it spawned a separate esports discipline. League of Legends, Dota 2, Heroes of the Storm — all grew from a Warcraft III map.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- One innovation can change a genre. Heroes in RTS seemed like a strange idea. Now it’s classic.

- Story matters even in strategies. Players want not just to win, but to empathize.

- Give tools to community. Good editor can create more content than entire studio.

- Balance isn’t just numbers. Uniqueness and character are more important than mathematical equality.

- Teach through play, not tutorials. Best learning is when player doesn’t notice they’re learning.

7. Civilization — Digital Drug

Lesson: How to create a game loop that’s impossible to break away from.

“One more turn” — this phrase has become a meme, symbol, and warning. Civilization isn’t just a game, it’s a test of willpower. A series that has destroyed more sleep schedules than all horror games combined.

History of Addiction

My introduction to the series began with the second part on PlayStation. Imagine: turn-based strategy, gamepad, TV instead of monitor. Seems like a recipe for disaster. But no — it worked. Moreover, it was so addictive that weekends flew by unnoticed.

Then came the third part on PC — square grid, beautiful graphics, improved diplomacy. University, fourth part with its rounded rhombus — I remember how my friend and I played co-op and suddenly discovered that:

- A month had passed

- An incredible number of classes were missed

- 20 kilograms gained (thanks to store salads)

I played the fifth part in snatches between work and graduate school. The sixth — you could say I didn’t play (50 hours for Civ doesn’t count). I didn’t launch the seventh out of self-preservation.

Formula of “One More Turn”

Why is Civilization so addictive? Sid Meier (series creator) describes it as “a constant stream of interesting decisions.” But that’s only part of the truth.

1. Multi-layered goals

- Now: scout explores ruins

- In 2 turns: city finishes building

- In 5 turns: research completes

- In 10 turns: can buy unit

- In 20 turns: wonder will be built

- Long-term: victory

There’s always something about to happen. It’s impossible to stop.

2. Illusion of control The game creates a feeling that you’re in complete control. Have a problem? Already figured out how to solve it. Just need to take one turn. Well, okay — ten. But definitely no more!

3. Absence of natural pauses No cutscenes. No loading between levels. No “end of chapter.” Turn flows into turn. Time disappears.

Civilopedia — Game Within a Game

The Civilopedia deserves separate mention — the built-in encyclopedia.

Educational value. It’s a complete reference on:

- History of technologies

- Biographies of great people

- Architecture of wonders

- Military affairs

- Philosophy and religion

Quotes. Each technology is accompanied by a quote. From Aristotle to Monty Python. They’re so good they’re remembered for years:

- “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

- “Corporation: an ingenious device for obtaining individual profit without individual responsibility” — Ambrose Bierce

- “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others” — Winston Churchill

Immersion. Reading Civilopedia, you begin to better understand the game’s logic. Why does monotheism lead to organized religion? Why does gunpowder change warfare? The game educates imperceptibly.

Series Evolution

Each Civilization part brought something new:

Civilization (1991) — laid the foundation. 4X in all its glory: eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate.

Civilization II (1996) — improved everything. Advisors, video inserts, scenarios. The one I played on PlayStation.

Civilization III (2001) — added culture and resources. Cities could switch to culturally dominant civilization.

Civilization IV (2005) — religion and great people. Transition to 3D. Leonard Nimoy voices technologies!

Civilization V (2010) — revolution. Hexagonal grid, one unit per tile, city-states. Controversial, but fresh.

Civilization VI (2016) — districts. Cities grow outward, not upward. Every placement decision is a puzzle.

Civilization VII (2025) — controversial decisions: attempt to divide game into eras with progress reset, leaders not tied to civilization.

“Snowball” Problem

All Civilizations have a common problem — at some point the game’s outcome becomes obvious.

Early game — every decision is critical. Where to place city? What to research? Warrior or worker?

Mid game — balance of power determined, but there’s intrigue. Wars, alliances, wonder races.

Late game — pure formality. You’re either hopelessly behind or so far ahead that victory is a matter of time. But you have to finish because… well, one more turn!

Multiplayer — Separate Universe

If single-player Civilization is meditation, multiplayer is chess on steroids.

Simultaneous turns change everything. Need to anticipate opponent’s actions. Will they move the warrior? Attack the city?

Diplomacy becomes real. Not negotiating with AI, but with a human. Bluff, threats, deals — just like real life.

Time matters. Turn timer adds tension. No time for Civilopedia — decide quickly.

Why It Works

Civilization uses several psychological mechanisms.

Zeigarnik effect — unfinished tasks are remembered better. There’s always something unfinished.

Variable reinforcement — rewards come irregularly. Sometimes ruins with gold, sometimes technology, sometimes great person.

Flow state — balance of difficulty and skills. Game adjusts to your level. Power and growth — from one settler to empire. Constant feeling of progress.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Create cycles of different lengths. Short-term, medium-term, and long-term goals should intersect.

- Remove natural pauses. The fewer reasons to stop, the longer the game session.

- Education through entertainment works. Players are ready to learn if it’s presented interestingly.

- Simple rules, complex consequences. Easy to start, impossible to fully master.

- Let players create history. Procedural generation + imagination = endless stories.

8. Hearthstone — Lesson in Systems Design

Lesson: How simple mechanics create infinite depth and why it’s addictive.

I got into collectible card games quite late. 2009, Blagoveshchensk, my friend Dmitry dragged me into Magic: The Gathering. Got hooked instantly, but returning to St. Petersburg, I realized — it’s an expensive pleasure.

Timeskip. 2014, Samui, evening after work. Stumbled upon a Hearthstone review on YouTube. Installed. Didn’t stop until I unlocked all classes. Over the next 11 years, Hearthstone became the game I invested the most time and money in.

Genius of Simplicity

With basic rule simplicity (mana grows automatically, attack by choice, maximum 7 creatures), Hearthstone hides incredible depth.

Each card is a mechanic. In one game you can use dozens of unique effects:

- Taunt — protects other creatures and hero

- Charge — attack immediately after playing

- Divine Shield — blocks first damage

- Deathrattle — effect on death

- Battlecry — effect when played

And these are basic mechanics. There’s also:

- Discover — choose from three random cards

- Inspire — effect when using hero power

- Overload — locked mana next turn

- Combo — enhanced effect if played another card

- And each expansion introduces at least one new mechanic

Synergies create strategies. Individual cards are simple. But together they create combinations. If I started listing and explaining them all, the article would grow to book size.

Psychology of Collecting

Hearthstone masterfully exploits human psychology.

Pack opening is loot boxes before they were criticized. Animation, sounds, anticipation — everything creates excitement. And when a legendary drops… That sound. That glow. Dopamine explosion.

Collection is never complete. Every 4 months — new expansion. 135 new cards. Old ones rotate to Wild format. Want to play Standard? Pay.

Golden cards. Functionally identical to regular ones, but animated. Status. Beauty. And there are also diamond and special cards.

Class system. 11 classes (originally 9, 2 added later), each with unique cards and strategies. Want to try everything? Collect everything.

Monetization as Art

Hearthstone makes billions. How?

Illusion of free-to-play. Technically, you can play for free. Practically — good luck building a competitive deck without investment. Actually: pay2win, but victory isn’t guaranteed.

Value obfuscation. Real money or Gold → Packs → Cards → Dust → Cards. With each step, connection to real money weakens.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). Some cards available for limited time. Didn’t get now? Later will be more expensive or impossible.

“Investments” in decks. Spent 5000 dust on a deck? When patch comes out, you’ll want to “protect investment” with upgrades.

Metagame as Living Organism

One reason for Hearthstone’s longevity — constantly changing metagame.

Discovery cycle. New expansion → experiments → optimal decks → counter-decks → stabilization → new expansion.

Nerfs and buffs. Blizzard actively intervenes. Deck too strong? Nerf key cards. Class weak? Buff. Expect balance patch within two weeks of each expansion.

Rotation. Standard format includes only cards from last two years. Metagame updates forcibly.

UX as Part of Magic

Hearthstone is a masterclass in game UX.

Physicality in digital world. Cards can be “touched” — they react to hovering, bend when dragged, “hit” when attacking.

Game board is a toy. Can click board elements. Launch catapult, squeeze vegetables, break crystals. Useless? Yes. Pleasant? Incredibly.

Animations tell story. Each legendary card has unique entrance animation. Ragnaros appears from flames. C’Thun grows with each cultist card played.

Sound. Card voicelines became memes, sometimes taken from memes. “Leeeeroy Jenkins!” “Everyone, get in here!” Recognizable from first second.

Evolution and Modes

Hearthstone didn’t stand still.

Adventures. Single-player campaigns with unique bosses and rewards. Way to sell content to PvE players.

Arena. Draft mode. Choose cards from random ones, build deck on the fly. Skill more important than collection.

Tavern Brawl. Weekly modes with crazy rules. All minions 1/1? Random deck each turn? Chaos and fun.

Battlegrounds. Auto-battler inside Hearthstone. So popular it overshadowed main mode.

Mercenaries. Attempt to make card battler. Failed, but indicative — Blizzard experiments.

Dark Side

Over 11 years I’ve seen how Hearthstone changes people.

Addiction. “Quick game before bed” turns into “it’s already 3 AM.”

Financial pit. I know people who spent tens of thousands of dollars. On digital cards.

Toxicity. Despite limited chat (only preset phrases or emojis), people find ways to be nasty.

Burnout. When hobby becomes obligation. Daily quests, seasonal rewards — work, not play.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Simplicity attracts, depth retains. Low entry barrier + high skill ceiling = success.

- Each mechanic is opportunity for synergy. Think systemically, not individual cards.

- UX isn’t decoration. It’s part of game experience. Tactility matters even digitally.

- Monetization is psychology. Understand player motivation, don’t exploit, but use.

- Metagame is living system. Plan changes, maintain interest.

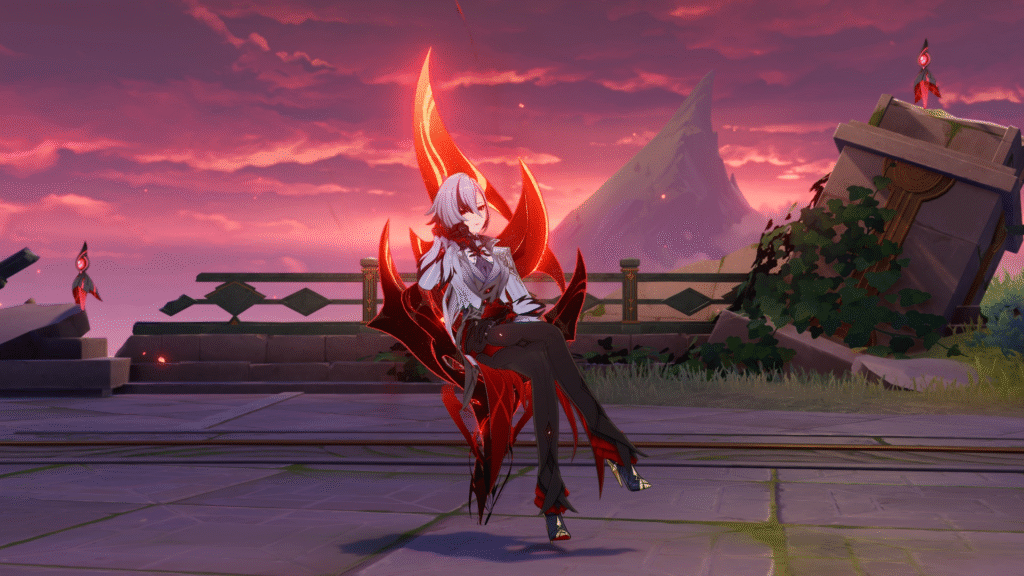

9. Genshin Impact — New Era Phenomenon

Lesson: How to sell a single-player game for the price of a car and make players thank you for it.

It’s 2025, and no one is surprised when someone spends a million dollars in a game. Usually we’re talking about multiplayer games where money gives advantage. But in 2020, Genshin Impact comes out — essentially a single-player adventure with gacha mechanics. And turns the industry upside down.

Perfect Storm of Factors

Why did Genshin Impact become a phenomenon?

Timing. Pandemic, lockdowns, loneliness. People sought escapism, new worlds, virtual relationships.

Quality. It’s a full AAA game at console exclusive level. Free.

Accessibility. PC, PlayStation, Xbox, Android, iOS. Cross-save. Play where you want, continue where convenient.

Anime aesthetic. Huge audience that was waiting for exactly this game. Beautiful characters, Japanese voice acting, recognizable tropes.

Monetization as Science

Genshin Impact perfected monetization.

Cost obfuscation:

- Real money → Genesis Crystals

- Crystals → Primogems

- Primogems → Intertwined Fates

- Fates → Wishes (gacha attempts)

With each step, connection to real money weakens.

Pity system. Genius move:

- 90 pulls — guaranteed 5-star reward

- 180 pulls — guaranteed banner character

- Progress saves between banners

This creates illusion of fairness. “I’m not losing money, I’m investing in guaranteed result.”

Constellations. Got character? Great! But they only fully unlock with 6 copies. Each copy — up to $360.

Signature weapon. Character without their weapon is like car without body. Works, but not as beautiful and convenient. Each copy — up to $320. And for maximum refinement need 5 copies.

Total: Fully upgraded character with weapon — about $4,120. Price of a used car.

Content as Conveyor

miHoYo created perfect content production machine.

Patches every 6 weeks. Like clockwork:

- One or two new characters

- New area or dungeon

- Story event

- Mini-games

Regions. Every year — new huge region. Mondstadt, Liyue, Inazuma, Sumeru, Fontaine, Natlan… And ahead at least Nod-Krai and Snezhnaya.

Events. Time-limited stories. Missed? Won’t see. FOMO in action.

Spiral Abyss and Theater. Only “endgame” content. Updates monthly. Requires different teams and strategies.

Psychology of Waifus and Husbandos

Genshin’s main secret — emotional attachment to characters.

Design. Each character crafted to smallest details:

- Unique appearance and animations

- Developed story and personality

- Voice acting in 4 languages

- Personal quests

Interactions. Characters don’t just stand in menu:

- Lines in different weather

- Dialogues about other characters

- Birthdays with letters

- Special dishes

Community. Fan art, fanfiction, cosplay. Characters live outside game. Twitter, Reddit, YouTube — fan content everywhere.

Parasocial relationships. For many players, characters aren’t just game assets. They’re friends, love interests, family. In a world of growing loneliness — valuable commodity.

Technical Perfection

Despite cynical monetization, can’t deny game quality.

Visuals. Game looks stunning even on phones. Art direction compensates technical limitations.

Music. Full orchestra. Each region has its own musical theme. Combat themes change dynamically.

Optimization. Runs on potato PCs and old phones. Yet on powerful hardware — beautiful.

Lack of bugs. For game of this scale — surprisingly few problems. QA department works excellently.

Industry Impact

How Genshin Impact changed the rules?

F2P quality. Can no longer release mediocre free games. Bar raised to heavens.

Gacha in open world. Before Genshin, gacha was realm of mobile battlers. Now it’s mainstream.

Investments. $100 million development cost recouped in two weeks. Other companies noticed.

Clones. Tower of Fantasy, Wuthering Waves, Honkai: Star Rail (from same miHoYo). Everyone wants to repeat success.

What It Teaches Game Designers

- Quality sells better than advertising. Word of mouth stronger than marketing.

- Emotional attachment = money. People pay for feelings, not mechanics.

- Content consistency is critical. Regularity more important than volume.

- Monetization is design. Can’t bolt it on later. Plan from start.

- Ethics matter. Can squeeze more money. But at what cost?

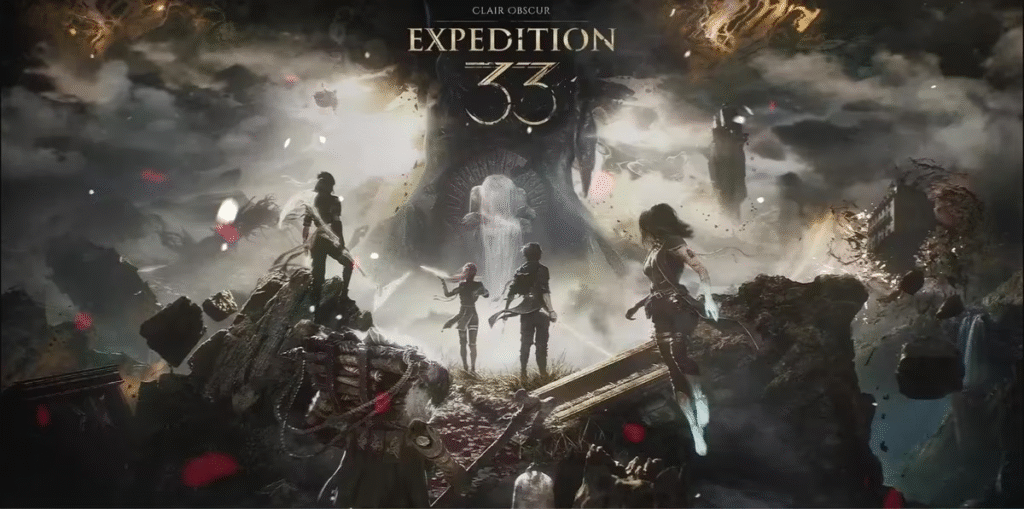

10. Current Hits — Industry Pulse

Lesson: Why it’s important to play what’s popular right now.

The last point isn’t a specific game, but a principle. Play what everyone’s talking about. Even if you don’t like it. Especially if you don’t like it.

Why It’s Important

Understanding audience. Millions of people can’t be wrong, at least not in game industry. If game is popular — it’s doing something right. Your task — understand what.

Current trends. Industry changes fast. What worked yesterday is outdated today. Hits show where market is moving.

Professional growth. Can’t discuss Baldur’s Gate 3 in 2025 interview? Minus karma. Don’t know why Palworld exploded internet? You’re behind industry.

Examples from Recent Years

Among Us (2020). 2018 game suddenly became hit. Why? Pandemic + streamers + sociality. Lesson: timing is everything.

Valheim (2021). Vikings, survival, co-op. Cozy hardcore. Lesson: contradictions can work.

Vampire Survivors (2022). Minimalist roguelike for $3 made millions. Lesson: gameplay more important than graphics.

Hogwarts Legacy (2023). Despite scandals, sold 20+ million copies. Lesson: IP power outweighs negativity.

Baldur’s Gate 3 (2023). Isometric RPG with turn-based combat became game of year. Lesson: quality beats trends.

Palworld (2024). “Pokemon with guns” got 25 million players. Lesson: familiar + unexpected = virality.

Black Myth: Wukong (2024). Chinese God of War broke all records. Lesson: regional games can go global.

How to Analyze Hits

Play minimum 10 hours. First impressions are deceptive. Give game a chance. Old rule about 2 hours doesn’t work anymore, many games have 10-hour tutorials.

Read reviews. Both positive and negative. Especially negative — often more informative.

Watch streams. How do people play? What hooks them? What moments are emotional?

Analyze mechanics. What’s new? What’s borrowed? How does it combine?

Study monetization. How does game make money? What motivates payment?

What to Look for in Hits

Needs. What need does game fulfill? Boredom? Loneliness? Achievement desire?

Innovations. Not necessarily revolutionary. Sometimes fresh combination of known is enough.

Accessibility. Low entry barrier often more important than depth.

Sociality. Even single-player games become social through streams and memes.

Timing. Why now? What in culture/society made game relevant?

Analysis Traps

“It’s just a clone of X.” Every game borrows something. Important HOW, not WHAT.

“Graphics are dated.” Minecraft still in top. Graphics aren’t main thing.

“It’s for casuals.” Casuals are majority. Ignoring them — losing money.

“Hype will pass.” Maybe. But while it’s here — study reasons.

Practical Application

For startups. Understand what can be done with small budget. Vampire Survivors — example.

For major studios. Study audience expectations. Baldur’s Gate 3 raised quality bar.

For everyone. Follow hybrids. Genshin Impact erased platform boundaries.

Instead of Conclusion

As always, this list isn’t dogma. There are no dogmas in game design. Every game designer will have their own set of important games. But the principle remains: play consciously, analyze systematically, learn constantly.

Games aren’t just entertainment. They’re a language we speak with players. And to speak well, you need to know classics, follow modernity, and understand why some games become phenomena while others are forgotten.

Great games teach not what to copy, but how to think. How to solve problems. How to create emotions. How to turn mechanics into stories, and stories into memories.

Play. Learn. Create.

P.S. What games are on your must-play list for game designers? What did I miss? What did I overrate? Let’s discuss in the Telegram chat https://t.me/GameGestaltChat_En